Archive \ Volume.11 2020 Issue 3

An Educational Intervention to Improve Adverse Drug Reaction Reporting: An Observational Study in a Tertiary Hospital in Vietnam

Vo TH 1*, Dang TN 2, Nguyen TT 3, Nguyen DT 4

1 Ph.D., Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. 2 Bsc, Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. 3 Msc, Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. 4 Ph.D., Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine, Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam.

Abstract

Context: Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADRs) are common. Aims: The study aimed to describe ADR reports after an educational intervention for physicians and nurses by clinical pharmacists. Methods and Material: Pharmacists conducted two separate training sessions for physicians and nurses in January and February 2019 in a tertiary hospital. The hospital collected all ADR reports from January to December 2019. Results: In 2019, the hospital reported 147 ADR cases, increasing 12.25 times compared to 2018. All ADR reports had complete information fields. The majority of ADR reports were collected by physicians (64.6%) and pharmacists (24.5%). The departments reporting the most ADRs were internal respiratory medicine (21.8%) and obstetrics (14.3%). Most ADRs were not serious (90.5%). The most-reported clinical signs were pruritus (64.0%) and erythema/redness (61.9%). All cases recovered without any complication after treatment. ADR reports were mainly related to the parenteral route (79.6%), and antibiotics (66.0%), analgesics (18.3%). Conclusions: Training of physicians and nurses by pharmacists on ADR significantly increased the quantity and quality of ADR reporting. More intensive and specific training and other measures are needed to improve the under-reporting of ADRs.

Keywords: hospital, reporting, ADR, pharmacovigilance, education

INTRODUCTION

The under-reporting of adverse drug reactions (ADR) is a challenge of pharmacovigilance in the world [1-3]. The median under-reporting rate across the 37 studies from 12 countries was 94% (interquartile range 82-98%) [2]. The major factors found to be responsible for underreporting of ADR include lack of knowledge and awareness of pharmacovigilance program [4], inadequate risk perception about newly marketed drugs, fear factor, lack of training programs for health care providers on pharmacovigilance, work overload [5].

Many initiatives to improve reporting include using information systems [6, 7], a hospital written policy [8], health care provider (HCP) reporting and direct patient reporting [9] as well as improved education and training of healthcare professionals [8, 10, 11]. Pharmacists have shown to play an important role in improving patient safety, including increasing the quantity and quality of ADR reporting in hospitals [12-14].

Vietnam launched its National Drug Information and Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Centre in 2009, a significant step towards catching up with international trends. The number of reports has increased rapidly, with some important signals generated from the national database leading to regulatory actions at a national level. Many opportunities remain to enhance the system, particularly in the evaluation of the impact of the intervention to improve ADR reporting [15].

Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital (NTPH) has stepped up cooperation with Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine (UPNT) in Ho Chi Minh in deploying clinical pharmacy since the beginning of 2019. One of the first missions of the clinical pharmacy unit at the hospital was to improve the quantity and quality of ADR reporting. This study aimed to describe the quantity and quality of ADR reporting in the hospital after an education intervention for physicians and nurses.

SUBJECTS AND METHODS:

Study design and setting

An observational study was carried over a period of 12 months from January to December 2019 in a tertiary teaching hospital (Nguyen Tri Phuong hospital - NTPH) at Ho Chi Minh, Vietnam. NTPH, the 800-bedded public teaching hospital offers both medical and surgical care. The average daily out-patient consultancy is 1500-2000 and in-patient is 100–200. To improve clinical pharmacy practice in NTPH, four lecturers on clinical pharmacy from the Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine have worked as part-time clinical pharmacists with four hospital clinical pharmacists in the Clinical Pharmacy Unit (CPU) in NTPH since January 2019.

Educational interventions

The Clinical Pharmacy Unit conducted 2 training sessions: one two-hour session was "Reporting of ADRs" on January 22, 2019, for nurses with the following main contents: (1) Introduction of common clinical manifestations of ADR in different organ systems, (2) List of patients at high risk of ADR to be monitored, (3) List of Drugs/drug groups with a high risk of ADR, (3) Benefits of ADR reporting in hospitals, and (4) ADR reporting process. The second one-hour session was "Diagnosis, Treatment, and Reporting of ADR" on February 27, 2019, for physicians focusing on the following topics: (1) Introduction of ADR clinical manifestations in organ systems, (2) high-risk factors for ADR, (3) Benefits of ADR reporting in hospitals, (4) ADR diagnosis and management, (5) ADR reporting procedures.

The functioning of the ADR reporting system

On daily basis, whenever HCPs suspected any symptoms/signs observed through the clinical review process of inpatients as a reaction to a drug(s), they reported in a national ADR notification form in paper [16] and sent it to clinical pharmacists. Pharmacists analyzed them for their completeness, credibility, and correctness. Data were carefully evaluated for quality, based on the following essential elements: patient initials, age, gender, date of reaction (onset), description of the reaction or problem, suspected medication(s), indications for use, concomitant medical products, severity, causality, de-challenge, re-challenge, management, and outcomes.

If additional details were required to collect by pharmacists or HCPs demanded pharmacists to visit clinical wards and manage clinical cases together, pharmacists would interview directly with the reporter and patients, and HCPs, and/or evaluation of patient medical records. Pharmacists collected information concerning previous allergies, concomitant medications, co-morbidities, and discussed with HCPs on ADR management. Suspected ADRs that met ADR reporting criteria were then sent via email to the national ADR center in Hanoi. Pharmacists wrote an ADR summary every 6 months and one year and sent them to HCPs in the hospital, and the hospital awarded one clinical department, which had the highest number of ADR reports at the end of the year.

Data collection

The reactions were categorized based on (1) reporter status (reporter, time, clinical department), (2) ADR characteristics (patient demographics (age and gender), organ system affected, severity, causality, outcome, and management), (3) drug characteristics (route of administration, drug groups, and drug name), and All data were collected by a national ADR reporting form [16]. We have assessed the causality to establish the relationship between the drug and the reaction by using the Naranjo scale [17]. All drugs were categorized according to the Anatomical Therapeutic Chemical (ATC) classification system and differentiated to the second level of the ATC code. The seriousness of the ADRs was assessed into 6 categories: death, life-threatening, hospitalization/prolongation of hospitalization, permanent or significant disability, fetal anomalies, and no severity [16]; ADR outcomes were classified as: fatal due to ADR, fatal not related to the drug, not recovered, recovering, recovered with complications, recovered without complications, and unknown. A method for estimating the causality of ADRs was Naranjo scale [17]: doubtful, possible, probable, definite, not yet classified, and unable to classify.

Ethical considerations:

The study was approved by the local antibiotic stewardship program board. The study was conducted in a spirit of respecting the private information related to patients and health care providers. Information, which was collected from routine data of drug charts was anonymized.

Statistical Analysis

All data were analyzed by using SPSS software version 20.0. Data were expressed in frequency, percentage, and mean ± SD.

RESULTS

Quantity and quality of ADR reporting and characteristics of reporters

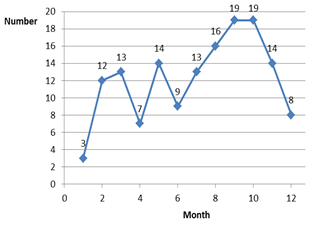

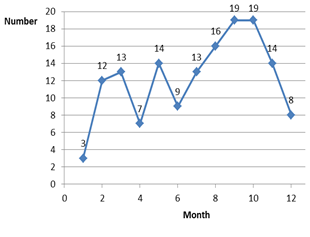

From January 1 to December 31, 2019, a total of 147 ADR reports were collected and reported to the National ADR Center, compared to 12 reports in the previous year (increased by 12.25 times). In particular, the report increased sharply from February when the two training sessions by pharmacist ended (Figure 1). The hospital reports an average of 12.25 ADR cases per month. All ADR reports were then reviewed by the clinical pharmacist before sending it to the national ADR center, thus ensuring 100% of ADR reports fill in the necessary information fields.

The majority of ADR reports were collected by physicians (accounting for 64.6%) and pharmacists (24.5%). All ADR reports were then reviewed by the clinical pharmacists to ask the reporter to supplement the missing information field and assess the causal relationship between the drug and reactions. The department reporting the most ADR was the department of internal respiratory medicine (21.8%) and obstetrics (14.3%) (Table 1).

Figure 1. Number of ADR reports by the month of 2019

|

Table 1. Characteristics of reporters of ADRs |

||

|

Parameter |

N |

Percentage (%) |

|

Reporters |

|

|

|

Reporter professional status |

|

|

|

Physician |

95 |

64,6 |

|

Pharmacist |

36 |

24,5 |

|

Nurse |

13 |

8,8 |

|

Medical assistant |

03 |

2,1 |

|

Clinical department |

|

|

|

Department of Respiratory Medicine |

32 |

21,8 |

|

Department of Obstetrics |

21 |

14,3 |

|

Neurology Surgery |

16 |

10,9 |

|

Emergency department |

10 |

6,8 |

|

Department of Cardiology internal medicine |

08 |

5,4 |

|

Department of anesthesiology and resuscitation |

08 |

5,4 |

|

Others |

52 |

35,4 |

Characteristics of ADRs

The majority of patients with ADR reported were 18-60 years old (64.0%) and female (64.0%). The most-reported manifestations were not serious (90.5%), which were pruritus (64.0%), erythema/redness (61.9%). Most cases recovered without complications (66.0%). The majority of ADRs were categorized as probable (49.7%) followed by possible (45.6%) in nature. The withdrawal of the offending drug and/or addition of other drugs to treat ADRs were common to manage ADRs (59.2% and 53.1%, respectively) (Table 2).

|

Table 2. Characteristics of ADR reporting (n=147) |

||

|

Parameter |

N |

Percentage (%) |

|

Patient profile |

|

|

|

Age group |

|

|

|

< 18 years |

1 |

0.7 |

|

18 - 60 years |

94 |

64.0 |

|

> 60 years |

52 |

35.3 |

|

Sex |

|

|

|

Male |

53 |

36.0 |

|

Female |

94 |

64.0 |

|

Characteristics of ADRs |

|

|

|

Severity |

|

|

|

No |

133 |

90.5 |

|

Hospitalization initial/prolonged |

4 |

2,7 |

|

Life-threatening |

10 |

6,8 |

|

Death |

0 |

0 |

|

Organ system involved |

|

|

|

Pruritus |

94 |

64,0 |

|

Rash erythematous/Rash/Urticaria |

91 |

61,9 |

|

Eye swelling/Eyelid edema/Eye edema |

17 |

11,6 |

|

Dyspnea |

15 |

10,2 |

|

Shiver/Chills |

12 |

8,2 |

|

Fever |

5 |

3,4 |

|

Hypotension |

5 |

3,4 |

|

Weak or absent pulse |

5 |

3,4 |

|

Others (purple lips, sweat, chest pain, facial numbness) |

9 |

6,1 |

|

Causality |

|

|

|

Doubtful |

4 |

2.7 |

|

Possible |

67 |

45.6 |

|

Probable |

73 |

49.7 |

|

Definite |

3 |

2.0 |

|

ADR management |

|

|

|

Addition of another drug to treat ADR symptoms |

87 |

59.2 |

|

Stop suspected drug(s) |

78 |

53.1 |

|

Change to another drug |

53 |

36.1 |

|

No change |

2 |

1.4 |

|

Dose or drug infusion reduced |

5 |

3.4 |

|

No information |

25 |

17.0 |

|

ADR outcomes |

|

|

|

Recovering |

50 |

34.0 |

|

Recovered without complications |

97 |

66.0 |

Characteristics of suspected drugs

All reported ADRs were related to intravenous injection (16/79,6%), oral (16/10.9%), rectal (9/6.1%), subcutaneous (3/2.0%), and hemodialysis (2/1.4%). A higher number of ADRs were reported for antibiotics 97 (66.0%) followed by analgesics and antipyretics, 27 (18.3%). A detailed list of offending drugs is shown in Table 3.

|

Table 3. Suspected drug groups and drugs of ADRs |

||||

|

Drug group |

Name |

N |

N |

% |

|

Antibiotics |

Levofloxacin |

35 |

97 |

66.0 |

|

Ceftriaxon |

19 |

|||

|

Vancomycin |

14 |

|||

|

Clindamycin |

5 |

|||

|

Imipenem + cilastatin |

4 |

|||

|

Ampicillin + Sulbactam |

3 |

|||

|

Moxifloxacin |

3 |

|||

|

Ciprofloxacin |

3 |

|||

|

Cefmetazol |

2 |

|||

|

Amoxicillin + Acid Clavulanic |

2 |

|||

|

Piperacillin + Tazobactam |

2 |

|||

|

Cefotaxim |

1 |

|||

|

Sparfloxacin |

1 |

|||

|

Ertapenem |

1 |

|||

|

Cefepime |

1 |

|||

|

Linezolid |

1 |

|||

|

Analgesics & Antipyretics |

Paracetamol |

14 |

27 |

18.3 |

|

Diclofenac |

10 |

|||

|

Celecoxib |

3 |

|||

|

Contrast agents |

Iohexol |

3 |

6 |

4.1 |

|

Iobitridol |

2 |

|||

|

Iodixanol |

1 |

|||

|

Other |

Amino acid |

1 |

23 |

15.6 |

|

Sodium chloride |

1 |

|||

|

Human albumin |

1 |

|||

|

Sitagliptin |

2 |

|||

|

Metoclopramide |

1 |

|||

|

Tranexamic acid |

2 |

|||

|

Immune globulin |

1 |

|||

|

Amino acids + peptides |

1 |

|||

|

Dialysis solution |

1 |

|||

|

Dobutamin |

1 |

|||

|

Lidocain |

2 |

|||

|

Hydrocortison |

1 |

|||

|

Acetyl leucine |

1 |

|||

|

Alfuzosin |

1 |

|||

|

Omeprazole |

1 |

|||

|

N-acetylcysteine |

2 |

|||

|

Colchicine |

2 |

|||

|

Erythropoietin |

1 |

|||

DISCUSSIONS

Quantity and quality of ADR reporting and characteristics of reporters

The knowledge and attitudes of physicians and nurses involved in ADR reporting are limited. A study of Lai QP [18] interviewed 683 Vietnamese doctors and nurses about perceptions, attitudes, and practice of pharmacovigilance in 2014 showed that 91.7% clinicians understood that reporting of ADRs was their responsibility but only 34.8% of staff knew the ADR reporting form, 82.1% of people encountered ADRs but only 40.3% ever reported ADRs. However, education on ADR reporting was provided by only 69 percent of pharmacy departments in the United Kingdom [13]. Our study confirmed that educational intervention tailored to physicians and nurses conducted by clinical pharmacists could increase significantly the number of ADR reporting rate.

The educational intervention helped to increase the number of ADR reported in 2019 by 12.25 times compared to 2018 (147 vs 12 reports). This was a very high increase compared to other interventions. A systematic review found that reports using information systems doubled the number of ADR reports [7]. The study of Herdeiro et al. stated that the workshop intervention increased the ADR reporting rate by an average of 4-fold while telephone interviews, in contrast, led to no significant difference (p = 0.052) [10]. One-hour educational outreach visits tailored to physicians also showed to increase in ADR reporting rates [19].

It is necessary to operate and constant interventions, which encourage ADR reporting [20]. Whereas telephone interventions only increased spontaneous reporting in the first 4 months of follow-up, workshops significantly increased both the quantity and relevance of spontaneous ADR reporting for more than 1 year [10]. In our study, the number of ADR reports had an increasing trend in the first 8 months of follow-up (from March to October) and started to decrease in the last two months (November and December).

The majority of ADR reports were collected by physicians (64.6%), but reporting by nurses was still limited (8.8%). This showed the very important role of physicians in reporting ADRs, especially in detecting and diagnosing ADRs. That was the reason why the training sessions were organized separately for doctors and nurses. The training session for physicians focused primarily on the principles of ADR diagnostic principles while one session for nurses focused primarily on suspected clinical manifestations of ADRs. In reality, in many cases, both nurses and physicians contributed to the reporting of ADRs, but only physicians who had higher status than nurses signed in the ADR form. These phenomena could explain why the proportion of ADR reporting by nurses was not as high as that by physicians.

Pharmacists were the second most common HCPs reported ADRs (24.5%). This reflected a fact that in many situations when an ADR was detected, a physician or nurse often called a clinical pharmacist to visit a clinical ward to assist them with ADR recording and discuss on how to manage the ADR, such as discontinuation of the drug, changing of drugs, the introduction of drugs to treat allergy symptoms, and changing of the rate of drug infusion. Thanks to these opportunities, physicians, and nurses change their perceptions on the role of clinical pharmacists in the promotion of safety and effectiveness of drug use [21, 22]. In the national report for the first 3 quarters of 2019, pharmacists accounted for 46.3% as reporter professional status [23], which showed Vietnamese pharmacists played a core role in pharmacovigilance activities.

Characteristics of ADR reports

ADR reporting is an ongoing and continuous process. Studies from the individual hospital help to identify the problems related to ADR reporting to resolve.

ADR is an important clinical problem for children. A systematic review found that incidence rates for ADRs causing hospital admission ranged from 0.4% to 10.3% of all children and from 0.6% to 16.8% of all children exposed to a drug during hospital stay [24]. Our study reported only one ADR related to children, which implicated that further interventions should target to improve ADR reporting in the pediatric population.

The need for early detection and reporting of serious ADRs was important because they may increase costs due to increased hospitalization, prolongation of hospital stay, additional investigations, and drug therapy, and mortality rate in more serious cases [25, 26]. The proportion of serious ADRs in our study was 9.5% with life-threatening (6.8%) and hospitalization/prolongation of hospitalization (2.7%). This result was similar to other studies, in which serious ADRs accounted for 5.1-12.6% of the total number of ADRs [26, 27]. However, the incidence of serious and fatal ADRs in hospitals was found to be extremely high in literature. Serious ADRs accounted for 6.7% of all hospital admissions and occurred in 10–20% of hospitalized patients [25]. For five of the eight hospital-based studies, the median under-reporting rate for more serious or severe ADRs remained high (95%) [2]. Ramesh et al. stated that factors that discouraged ADR reporting were well-known reactions, mild reactions, and immediate management of ADRs [20].

The ADR manifestations collected in the hospital were mainly noticeable signs related to drug allergic reactions. The most common clinical presentation involved was skin and subcutaneous tissue disorders with pruritus (64,0%), rash erythematous/rash/urticaria (61,9%), followed by anaphylactic shock, fever, chills; which was similar to another study [28]. However, many other ADRs, such as hemodynamic changes, elevated liver enzymes, and renal failure, bleeding, etc. have not been reported. This indicated that pharmacists need to focus the next training for HCPs on how to recognize and report ADRs on specific organ systems.

Drugs involved in ADRs

ADR reports were mainly related to the parenteral route, accounting for 79.6%, higher than 48.6%, the rate recorded from the national summary [23]. Antibiotics and analgesics and antipyretics comprised the major groups of drugs causing ADRs (66.0% and 18,3%, respectively). Among them, the drugs most suspected to cause ADR were levofloxacin (35 cases), ceftriaxone (19 cases), vancomycin (14 cases), and paracetamol (14 cases). The study of Venkatasubbaiah et al. found that a higher number of ADRs were reported for antibiotics, followed by antipsychotics, analgesics, and antipyretics [27]. The study of Pathak et al. revealed that antibiotics and anticancer drugs are the most common drugs implicated [29]. In summary, antibiotics were more commonly implicated in ADRs [28]. A total of 298 (20%) patients experienced at least 1 antibiotic-associated ADE. The study of Tamma et al. in 2017 found that 20% of hospitalized patients receiving at least 24 hours of antibiotic therapy developed an antibiotic-associated ADR [30]. Some activities of the CPU include patient ward rounds, writing local drug use protocol (such as therapeutic drug monitoring of vancomycin), medication review [31], educational interventions [32], drug information, and ADR management. Further educational interventions should focus on how to reduce and manage ADRs related to antibiotics, and specific drug groups.

CONCLUSIONS

Training for physicians and nurses by pharmacists on diagnosis, reporting, and treatment of ADRs helped to increase the number of ADR reports by more than 12 times. More intensive and specific training and other measures are needed to solve under-reporting ADRs.

Abbreviations

HCP: health care provider

ADR: Adverse drug reaction

NTPH: Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital

UPNT: Pham Ngoc Thach University of Medicine

CPU: Clinical Pharmacy Unit

ACKNOWLEDGMENT

The authors gratefully acknowledge Nguyen Tri Phuong Hospital for their support of the implementation of the research. They also would like to express their deep gratitude to all the health care providers for their contribution to the study.

REFERENCES

- Tandon VR, Mahajan V, Khajuria V, Gillani Z. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a challenge for pharmacovigilance in India. Indian J Pharmacol. Jan-Feb 2015;47(1):65-7

- Hazell L, Shakir SA. Under-reporting of adverse drug reactions: a systematic review. Drug Saf. 2006;29(5):385-396.

- Zaaba NA, Roy A, Lakshmi T. Perception of women on the adverse effect of drugs on the fetus during pregnancy. J. Adv. Pharm. Educ. Res. 2017;7(2):72-5.

- Aziz Z, Siang TC, Badarudin NS. Reporting of adverse drug reactions: predictors of under-reporting in Malaysia. Pharmacoepidemiol Drug Saf. Feb 2007;16(2):223-228.

- Khan SA, Goyal C, Chandel N, Rafi M. Knowledge, attitudes, and practice of doctors to adverse drug reaction reporting in a teaching hospital in India: An observational study. J Nat Sci Biol Med. Jan 2013;4(1):191-196.

- Ribeiro-Vaz I, Santos C, da Costa-Pereira A, Cruz-Correia R. Promoting spontaneous adverse drug reaction reporting in hospitals using a hyperlink to the online reporting form: an ecological study in Portugal. Drug Saf. May 1 2012;35(5):387-394.

- Ribeiro-Vaz I, Silva AM, Costa Santos C, Cruz-Correia R. How to promote adverse drug reaction reports using information systems - a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2016;16:2

- Sweis D, Wong IC. A survey on factors that could affect adverse drug reaction reporting according to hospital pharmacists in Great Britain. Drug Saf. Aug 2000;23(2):165-172.

- Avery AJ, Anderson C, Bond CM, et al. Evaluation of patient reporting of adverse drug reactions to the UK 'Yellow Card Scheme': literature review, descriptive and qualitative analyses, and questionnaire surveys. Health Technol Assess. May 2011;15(20):1-234, iii-iv.

- Herdeiro MT, Ribeiro-Vaz I, Ferreira M, Polonia J, Falcao A, Figueiras A. Workshop- and telephone-based interventions to improve adverse drug reaction reporting: a cluster-randomized trial in Portugal. Drug Saf. Aug 1 2012;35(8):655-665.

- Sundus A, Ismail NE, Gnanasan S. Exploration of healthcare practitioner’s perception regarding pharmacist’s role in cancer palliative care, Malaysia. Pharmacophores. 2018;9(4):1-7.

- van Grootheest AC, de Jong-van den Berg LT. The role of hospital and community pharmacists in pharmacovigilance. Res Social Adm Pharm. Mar 2005;1(1):126-133.

- Ferguson M, Dhillon S. A survey of adverse drug reaction reporting by hospital pharmacists to the Committee on Safety of Medicines — the role of pharmacy departments. International Journal of Pharmacy Practice. 1999;7(3):167-171.

- Dubey R, Upmanyu N. Role of pharmacist in pharmaceutical waste management. World Journal of Environmental Biosciences. 2017;6(2):1-3.

- Nguyen KD, Nguyen PT, Nguyen HA, et al. Overview of Pharmacovigilance System in Vietnam: Lessons Learned in a Resource-Restricted Country. Drug Saf. Feb 2018;41(2):151-159.

- Vietnam National Drug Information and Adverse Drug Reaction Monitoring Centre. [How to report ADR]. http://canhgiacduoc.org.vn/CanhGiacDuoc/howtoreportadr.aspx. Accessed Feb 21, 2020.

- Naranjo CA, Busto U, Sellers EM, et al. A method for estimating the probability of adverse drug reactions. Clin Pharmacol Ther. Aug 1981;30(2):239-245.

- Lai QP. [Survey of ADR reporting on pediatric patients in the national database and perceptions, attitudes of health care providers on pharmacovigilance activities in some pediatric hospitals] [Bachelor Thesis], Hanoi Univeristy of Pharmacy; 2014.

- Figueiras A, Herdeiro MT, Polonia J, Gestal-Otero JJ. An educational intervention to improve physician reporting of adverse drug reactions: a cluster-randomized controlled trial. JAMA. Sep 6 2006;296(9):1086-1093.

- Ramesh M, Parthasarathi G. Adverse drug reactions reporting: attitudes and perceptions of medical practitioners. Asian Journal of Pharmaceutical and Clinical Research. 2009;2(2):10-14.

- AlOsaimi KM, Kambal AM, AlOtaibi FM, AL-Anazi AB, AlMotairi AR, AlGhamdi WM, Altujjar AR. Factors Affecting Physicians' Choice of Antibiotics for Treatment of Community-Acquired Urinary Tract Infections and Their Correlation with Antimicrobial Susceptibility Test Results in King Khalid University Hospital during 2013-2014. Int. J. Pharm. Res. Allied Sci. 2018;7(1):119-25.

- Atia A. Physician Trends of Drug Prescription in Libya: A Pharmacoepidemiological Study. Pharmacophores. 2019;10(3):33-8.

- Tran NH. [Summary of ADR reporting activities from November 2018 to July 2019]. [Journal of Pharmacovigilance]. 2019.

- Smyth RM, Gargon E, Kirkham J, et al. Adverse drug reactions in children--a systematic review. PLoS One. 2012;7(3):e24061.

- Lazarou J, Pomeranz BH, Corey PN. Incidence of adverse drug reactions in hospitalized patients: a meta-analysis of prospective studies. JAMA. Apr 15 1998;279(15):1200-1205.

- Prajapati K, Desai M, Shah S, Panchal J, Kapadia J, Dikshit R. An analysis of serious adverse drug reactions at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Perspect Clin Res. Oct-Dec 2016;7(4):181-186.

- Venkatasubbaiah M, Reddy PD, Satyanarayana SV. Analysis and reporting of adverse drug reactions at a tertiary care teaching hospital. Alexandria Journal of Medicine. 2018;54(4):597-603.

- Priyadharsini R, Surendiran A, Adithan C, Sreenivasan S, Sahoo FK. A study of adverse drug reactions in pediatric patients. J Pharmacol Pharmacother. Oct 2011;2(4):277-280.

- Pathak AK, Kumar M, Dokania S, Mohan L, Dikshit H. A Retrospective Analysis of Reporting of Adverse Drug Reactions in a Tertiary Care Teaching Hospital: One Year Survey. J Clin Diagn Res. Aug 2016;10(8):FC01-04.

- Tamma PD, Avdic E, Li DX, Dzintars K, Cosgrove SE. Association of Adverse Events With Antibiotic Use in Hospitalized Patients. JAMA Internal Medicine. 2017;177(9):1308-1315.

- Vo TH, Hoang TL, Faller EM, Nguyen DT. Development and validation of the VI – MED® tool for medication review. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2020;10(2):086-096.

- Le TQ, Le TMN, Vo THP, et al. Effectiveness of Educational Intervention on Knowledge and counseling practice on common cold management among community pharmacists. Journal of Applied Pharmaceutical Science. 2020;10(5):119-126.